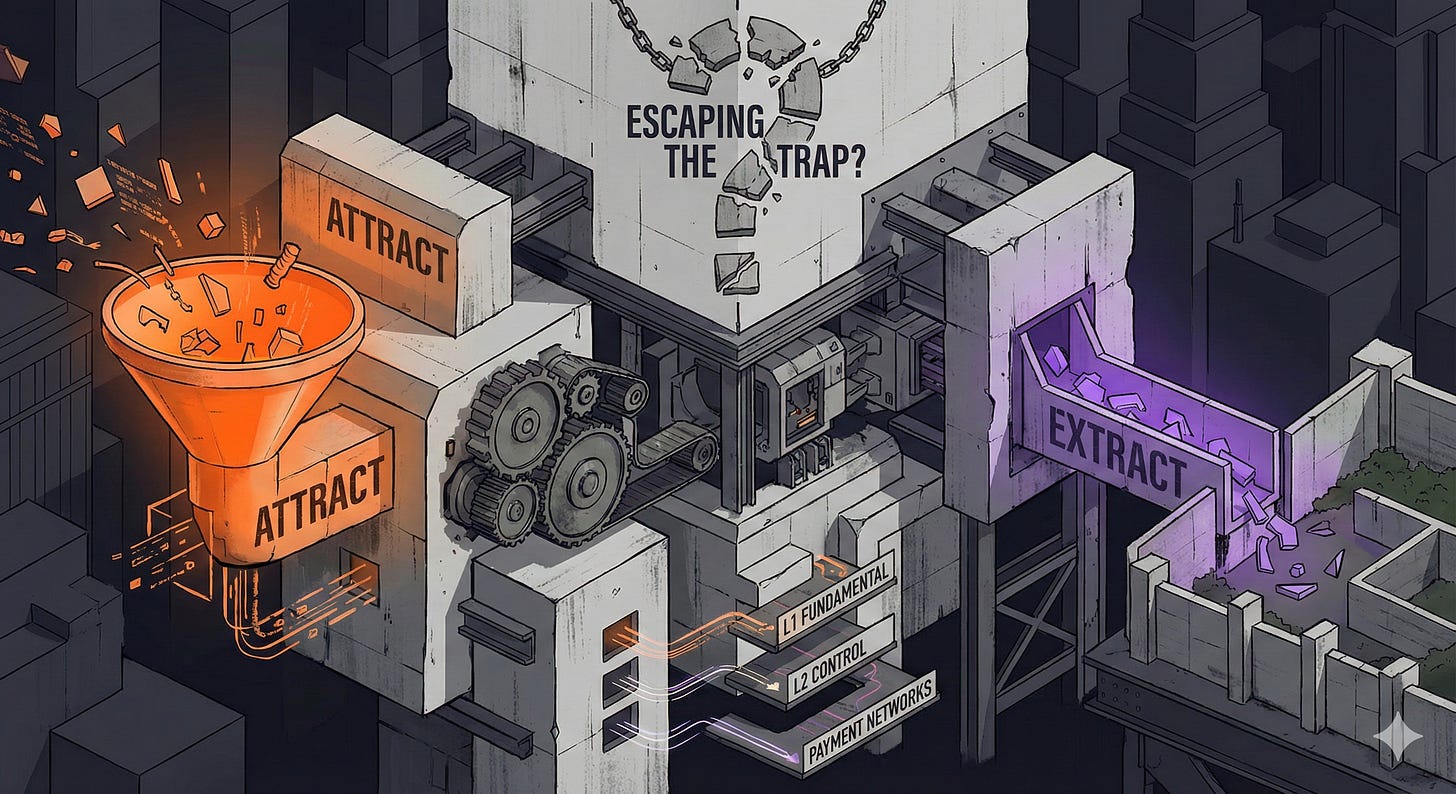

Are We Actually Escaping the Attract-Extract Trap?

Base, Arc, Tempo: Who really controls your ‘decentralised’ rollup - and does it matter?

Chris Dixon’s “Read, Write, Own” gave us a framework everyone loves to cite: the attract-extract cycle. Platforms pour money into growth, cultivate

network effects, then flip the script—extracting value from the same users who made them valuable. Facebook perfected it. Google institutionalised it. Visa and Mastercard turned it into a $500 billion business model.

Blockchain technology promised to break this cycle. Community-owned networks. Aligned incentives. Value flowing to participants, not just shareholders.

But here’s what nobody wants to talk about: Are we actually escaping this trap, or are we building shinier versions of the same extractive systems—just with better marketing and a token?

I’ve spent enough time in this space to recognise when we’re telling ourselves comforting stories. The discomfort that follows is worth sitting with.

The Ethereum Question

Start with what we call the most decentralised smart contract platform: Ethereum.

Post-merge, the narrative is “decentralised enough.” But look at the numbers.

Lido commands roughly 30% of staked ETH. Add Coinbase, Kraken, and Binance, and you’ve got a handful of entities controlling the majority of validation power. This isn’t speculation - it’s on-chain data anyone can verify.

Does this make Ethereum centralised? Not quite. The protocol remains credibly neutral. Anyone can stake. The rules are transparent. No single entity can unilaterally change the system.

But here’s what decentralisation maximalists miss:

First uncomfortable question: If value accrues to large staking entities, have we escaped the attract-extract dynamic - or just rotated who does the extracting?

The L2 Control Problem

If Ethereum’s decentralisation is debatable, L2s make the question unavoidable.

Look at who’s building the dominant rollups:

Base - Coinbase (a public company with shareholder obligations)

Arc - Circle (issues the second-largest stablecoin)

Tempo - Stripe and Paradigm (processes a meaningful chunk of internet commerce)

These aren’t anonymous cypherpunks hacking in basements. These are the same institutions that dominate traditional finance - the ones blockchain was supposed to disintermediate.

I work in this space. I believe many of these teams genuinely want to build better systems. But let’s be brutally honest about the structure:

Who controls the sequencer? Who decides transaction ordering? Who captures MEV?

These questions determine who extracts value. Right now, the answer is: centralised operators with “decentralisation roadmaps.”

“We’ll decentralise... eventually.” Sound familiar? It’s the exact language every platform uses during its attract phase. Twitter was going to be an open protocol. Facebook was about connecting people. Now they’re attention-extraction machines.

Second uncomfortable question: Are L2s “decentralised” because they settle to Ethereum, or are they centralised platforms with decentralised exit options?

The bull case says exit options matter - if Base gets extractive, bridge to Arbitrum. The bear case says network effects and liquidity make migration costly enough that exit rights are theoretical, not practical.

“In Brazil, we watched this play out with PIX. The instant payment system is technically open, but Nubank and a handful of banks captured the network effects. Theoretical openness, practical concentration. The pattern repeats.”

The Missing Layer: Blockchains vs. Payment Networks

Here’s where it gets interesting - and more uncomfortable.

A blockchain is a network with:

Technical infrastructure (nodes, consensus, execution)

Economic incentives (tokens, fees, staking rewards)

But a payment network requires layers that blockchains don’t provide:

Rules governing relationships between parties

Dispute resolution mechanisms

Compliance and identity frameworks

Merchant acceptance and consumer protection

Visa isn’t just infrastructure. It’s a dense web of rules, agreements, and guarantees layered on top of infrastructure.

Circle just launched the Circle Payments Network--explicitly a network on top of blockchain networks, providing the relationship layer that raw blockchain infrastructure lacks.

Fundamental question: If value increasingly moves to these overlay networks, does the underlying blockchain’s decentralisation even matter?

Think it through: You’re on a “decentralised” L2, but your payment flows through Circle’s network, which sets its own rules for participation, fees, and dispute resolution.

The blockchain is decentralised. The payment network on top is not.

The Layering Paradox

The emerging stack looks like this:

[Payment Networks: Circle, etc.] - Rules, relationships, compliance

|

[L2s: Base, Arc, Tempo] - Execution, settlement guarantees

|

[Ethereum L1] - Security, data availability

Each layer has distinct control characteristics:

L1: Relatively decentralised (with concentration concerns)

L2: Mostly centralised today (with decentralisation promises)

Payment Networks: Corporate-controlled (with blockchain optionality)

The promise of community-owned payment systems assumes alignment across all layers. But what if the layers have conflicting incentives?

“Are we building decentralized rails for centralized applications? And if so, is that actually better than what exists today?”

Maybe it is. Maybe transparent extractive systems beat opaque ones. But let’s not pretend we’ve solved the problem.

The Case for Cautious Optimism

I don’t want to be purely cynical. Real differences from the web2 playbook exist:

Exit rights matter. Even imperfect exit options change game theory. Visa can’t let you migrate transaction history to Mastercard. Blockchain systems make this theoretically possible--and theoretical possibilities constrain behaviour.

Transparency changes incentives. When fee structures live on-chain, you can’t quietly raise take rates. The attract-extract pivot becomes visible, and visibility creates accountability.

Composability creates alternatives. If Circle becomes extractive, competing payment networks can plug into the same rails. Infrastructure is shared even when applications aren’t.

But I’m not convinced these add up to “escaping” the trap. More like “making the trap visible and somewhat escapable.” That’s progress. It’s not victory.

Questions Worth Asking

I started writing this expecting to arrive at a thesis. Instead, I arrived at questions:

What’s the minimum viable decentralisation for a payment network? Does every layer need decentralisation, or is one layer sufficient?

Who captures value in a layered system? If L1 is decentralised but L2 and payment networks aren’t, who actually benefits from “community ownership”?

Is “decentralise later” a legitimate roadmap or a marketing strategy? How do we distinguish genuine plans from perpetual promises?

Does blockchain optionality matter if switching costs are prohibitive? Exit rights only work if exit is practical.

Are we building for user sovereignty or institutional efficiency? These might not be the same thing--and we should stop pretending they are.

Final Thoughts

Chris Dixon’s framework is useful. The attract-extract cycle is real, and blockchain technology genuinely offers new tools for building networks differently.

But “offers tools” is not “has solved.”

The honest assessment: we’re in an uncertain middle. Some parts of the stack are genuinely more decentralised than their web2 equivalents. Other parts are just as concentrated—or more so.

The promise of community-owned payment systems remains just that. Whether it becomes reality depends on decisions not yet made by entities with their own incentives—ones that may not align with ours.

That’s worth naming. Not to be pessimistic, but to be honest about where we actually are.

The trap is well understood. Whether we escape it remains an open question.

What’s your read? Are L2 decentralisation roadmaps credible, or are we watching the attract phase of a familiar cycle? I’d love to hear your perspective in the comments.